Dive Brief:

- COP29 wrapped up over the weekend with a deal to provide developing countries $300 billion in climate financing annually by 2035 to help cope with the adverse impacts of climate change. However, the commitment has been labeled as a “failure” by environmental groups and vulnerable nations alike.

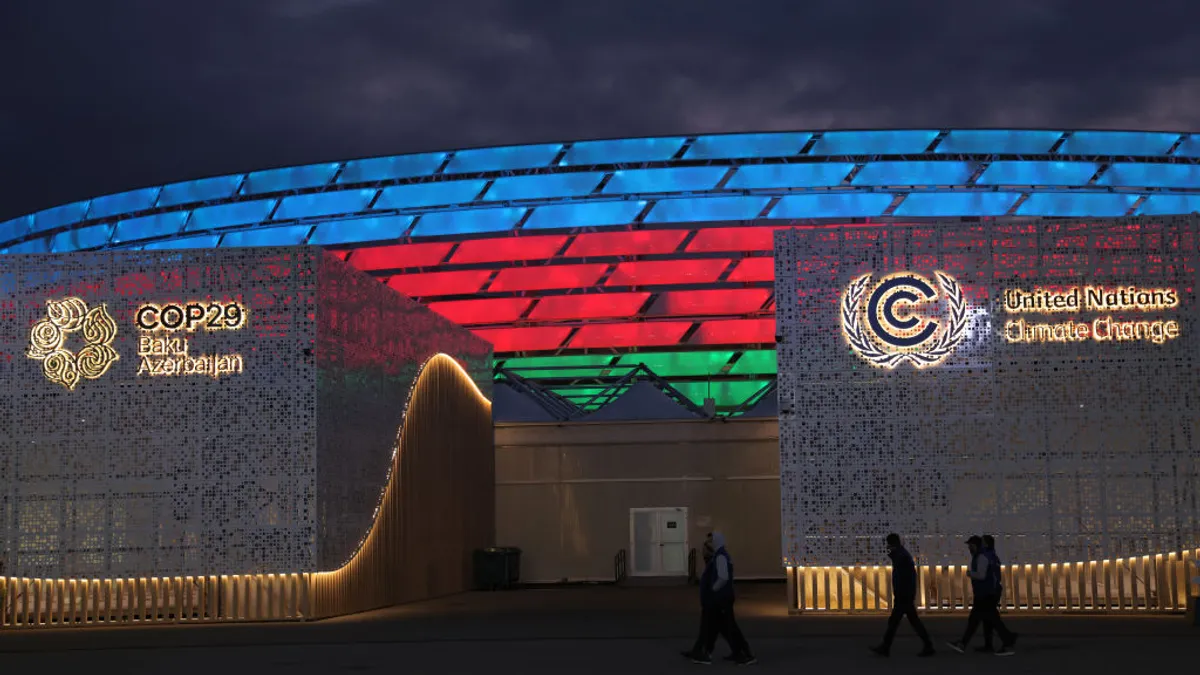

- The deal was announced Sunday, two days after the summit was originally scheduled to conclude, and followed two weeks of contentious discussions between negotiators present at the Baku, Azerbaijan venue.

- The goal expands on a previous commitment that wealthier nations made at COP15 in 2009 to funnel $100 billion per year to climate-imperiled nations by 2020. The nations met this target two years late, in 2022, and the majority of financing came from loans, according to a recent analysis from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Dive Insight:

The annual financing commitment is part of the Baku Finance Goal, which will seek to provide the nations most vulnerable to climate change a collective $1.3 trillion by 2035. This will be met by scaling up financial contributions from public and private sources to “at least” $300 billion per year, per the final goal.

COP29 President-designate Mukhtar Babayev called the commitment a “breakthrough,” despite his final proposal noting that the estimated climate adaptation finance needs for developing countries range between $215 billion to $387 billion annually until 2030. The final proposal also highlighted the “gap between climate finance flows and needs,” especially for the countries most impacted by climate change.

“The Baku Finance Goal represents the best possible deal we could reach, and we have pushed the donor countries as far as possible,” Babayev said in a Nov. 24 statement accompanying the final deal. “We have forever changed the global financial architecture and taken a significant step towards delivering the means to deliver a pathway to 1.5°C.”

The $300 billion pledge stands in stark contrast to the estimated price tag of meeting climate and development goals, which experts project to be as high as $1 trillion a year. The figure is based on the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance’s 2023 report, which also found that global climate finance flows are “still too low” compared to what is needed to accelerate a clean energy transition and build resilience to climate-driven events.

Environmentalists, climate groups and developing nations were quick to lambaste the final deal.

“Powerful nations have shown no leadership, no ambition, and no regard for the lives of billions of people on the frontlines of the climate crisis,” a bloc representing the 45 nations most vulnerable to climate change — including Bangladesh, Haiti, Ethiopia — said in a Sunday statement. “This is not just a failure; it is a betrayal.”

The World Wildlife Fund echoed this sentiment and called the finance deal “weak” and a “setback for climate action.”

“The world has been let down by this weak climate finance deal,” WWF Global Climate and Energy Lead Manuel Pulgar-Vidal said in a Nov. 24 release. “At this pivotal moment for the planet, this failure threatens to set back global efforts to tackle the climate crisis. And it risks leaving vulnerable communities exposed to an onslaught of escalating climate catastrophes.”

UN Secretary-General António Guterres also issued a statement Saturday, a few hours before the final deal was announced, and said he had “hoped for a more ambitious outcome — on both finance and mitigation.”