Packaging is going through one of the biggest states of change in decades, largely driven by enhanced sustainability efforts and legislation. But change isn't easy and often fuels confusion. Experts say it's time for industry to clear things up regarding sustainable packaging.

Greenwashing, when companies make false or inflated environmental claims about their products, is a known issue and has spawned the newer term greenhushing, when companies keep quiet about their sustainability work to avoid greenwashing claims. This can cause confusion and erode consumer trust, said Suzanne Shelton, senior partner at Shelton Group, an ERM Group company, during the SPC Advance event in Chicago last week.

But besides overt greenwashing, companies' abundant and different sustainability information on their product packaging is sending mixed messages, sources say. Part of the problem is the lack of a singular definition for “sustainable,” both from brands’ and consumers’ perspectives, said speakers at recent industry events.

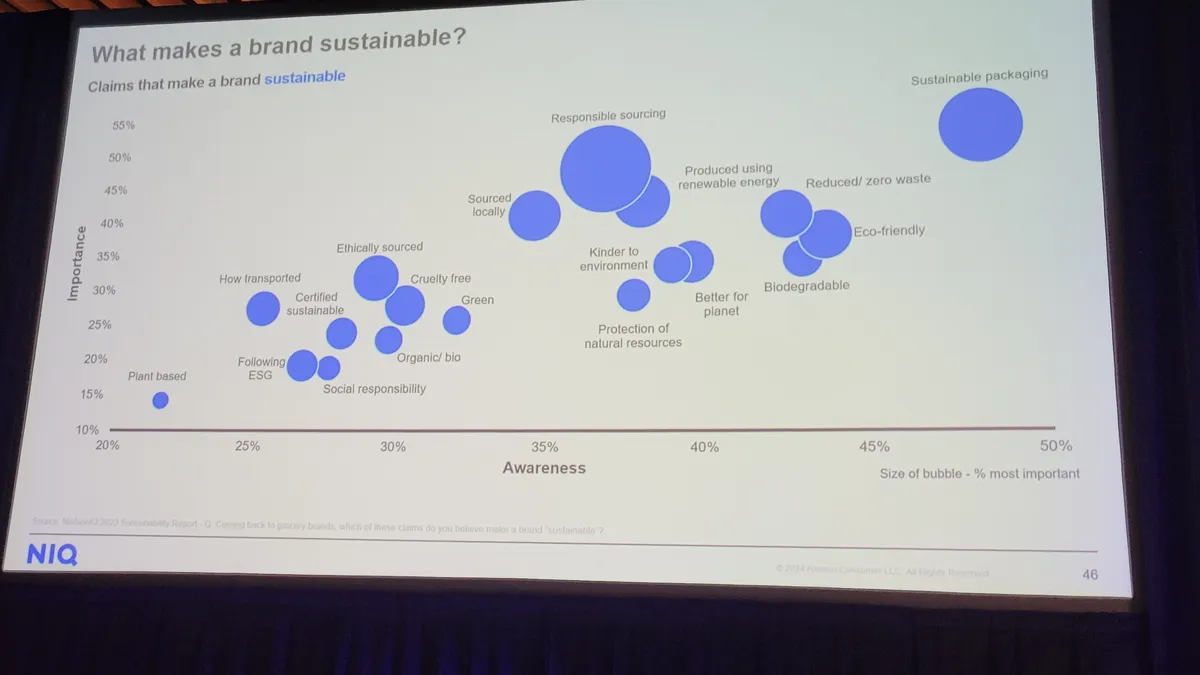

When asked what makes a brand sustainable, consumers' responses widely varied and included mentions of packaging, responsible sourcing and renewable energy, according to NielsenIQ's 2023 consumer packaged goods sustainability report. Confusing or unavailable information was the third-largest barrier consumers reported that stopped them from adopting a more sustainable lifestyle, behind cost and lack of sustainable product availability.

Consumer Packaged Goods put a plethora of different sustainability-oriented messaging on their packaging, and it's difficult for consumers to figure out the true meanings, said Kasra Eskandari, associate director of sales for packaging at Nielsen IQ, during the Packaging Recycling Summit in Atlanta on Sept. 16. Some categories had a "massive amount of claims currently on the package," he said. Plus, the number of claims continues to grow.

“It's actually very, very confusing to consumers. What do all these things actually mean?” Eskandari said.

Packaging is not among the largest impacts to companies' carbon footprints for most products, compared with the rest of the value chain, said Scot Case, vice president of corporate social responsibility and sustainability at the National Retail Federation, during E-PACK in Chicago last week. But that's not the impression consumers get. “Consumers began focusing more and more on packaging, and retailers have absolutely responded,” Case said. “They're communicating about packaging because that's what the consumers understand.”

Recycling is a main area of confusion. The term “recyclable” showed up in more than 1,200 of the 1,400 product categories NielsenIQ examined in 2023. But, similar to sustainability, various people hold different perceptions of what recycling or recyclability means.

“There's this interesting disconnect: For as freaked out as we are about climate, what we understand is packaging and recycling and reuse,” Shelton said. “And some of that is because that’s the message we’ve been giving them.”

On recyclability messaging, Case described disparities even with the definition of the term recyclable. “It's no longer just acceptable to say we can collect it for recycling if it's not actually recycled into new products,” he said.

Numerous speakers at recent conferences highlighted consumers' waning faith in recycling, both nationally and locally, following years of news reports that various parts of the system are “broken.” According to a recent survey Shelton's company conducted of U.S. consumers, 32% of respondents no longer believe the items they put in a recycling bin are getting recycled; that's up from 14% just four years prior.

Turning around that trend again largely goes back to messaging, she said.

“I believe we're in the middle of solving this problem ... So I think it's incumbent on all of us to encourage them to hang in,” Shelton said. “People want to believe in recycling; you need to help make them believe. You need to help fix the system and then help them believe that the system is real and they should continue participating.”

Consumers expect all of their packaging to be recyclable, but “the infrastructure simply isn't there,” Case said. “And that's why we see more and more legislators looking at things like extended producer responsibility.”

Consumers report trying to live in a more sustainable manner, with 69% saying sustainability has become more important to them in the last two years, according to NielsenIQ's data. But confusion can stunt their action when it comes to recycling and purchasing products with more sustainable packaging. CPGs and retailers must help the public sort out all the different claims, and in a truthful way, sources say.

“[Consumers] need manufacturers to educate them on the impacts of their products,” said Eskandari. Standardized language on packaging will help, and that’s likely to occur — at least to some degree — as regulations such as extended producer responsibility come down the pike, he said.

People are beginning to rethink the role of packaging and the messaging on it in the context of broader sustainability systems, according to Case.

“The biggest piece? Think systemically ... Make sure [you're] part of a broader sustainability story,” Case said. “If the conversation you're having with retailers is focused only on the sustainability of this box or this type of packaging, you're not talking the language.”

In the end, turning the tide on consumer understanding of sustainable packaging comes down to product manufacturers, not the public, sources said.

“You need to continue to talk to them about recycled content and recyclability, but the onus is on all of you to lean into the bigger issues,” Shelton said. “They're expecting you guys to solve these problems.”